MISHPATIM: La Torá, Hammurabi y los derechos humanos

DERECHOS DEL ESCLAVO?

La Parashá de esta semana, Mishpatim, contiene una gran cantidad de leyes en lo que constituye el primer código de la ley judía después de los Diez Mandamientos. Vale la pena analizar la primera de estas leyes, la del esclavo hebreo (עבד עברי). Cuando un hombre es vendido como sirviente —generalmente de manera voluntaria debido a una pobreza extrema, o porque robo y no tienen los medios para pagar su deuda. La Torá menciona algunos de los detalles de la relación entre el amo y el sirviente. Pero sorprendentemente, especialmente para esa época y contexto, la Tora NO se refiere en absoluto a las obligaciones de los esclavos hacia sus amos, sino a otra cosa, completamente inesperada y prácticamente inexistente en esto tiempos: los derechos del esclavo. Por ejemplo: la cantidad máxima de años que puede trabajar un esclavo; sus derechos conyugales, que permanecen vigentes durante la esclavitud; su derecho a ser tratado humanamente y con dignidad, e incluso su derecho a una indemnización después de que termine la esclavitud. Recuerden que estas leyes se están presentando a personas que hasta hace unas semanas atrás habían sido «esclavos» del tirano Faraón. Y en Egipto fueron tratados con violencia y humillación, y se les privó de todos los derechos básicos. Ahora, en unos años, al ingresar a la Tierra Prometida, muchas de estas personas podrán tener sus propios esclavos. Serán “amos», porque la esclavitud, especialmente la servidumbre voluntaria, (indentured servant), era muy común en esos días.

ROMPIENDO EL CIRCULO VICIOSO

Tratemos de imaginar ahora el impacto psicológico de esta «declaración de derechos humanos» en la mente de los hebreos. Al mencionar la esclavitud, hay un reconocimiento del trauma que los judíos soportaron durante más de dos siglos. Pero la Ley Divina ahora requiere superar la peligrosa tendencia a la auto-victimización y el resentimiento. Y propone un cambio de paradigma, difícil, pero no imposible. Es como si Dios le dijera a su pueblo elegido: “Lo que has vivido en el pasado, lo que has sufrido, no puede condicionar tu comportamiento con tus propios trabajadores. Los egipcios abusaron de ti, pero ese trato fue incorrecto. Lo condeno, pero también lo prohíbo. El abuso no se puede repetir. Lo peor que podría pasarte es que debido a que fuiste abusado, ahora te conviertas en un abusador. Por lo tanto, te estoy enseñando que cuando los roles se inviertan y te conviertas en un “patrón», no debes repetir el comportamiento de tus opresores «. La Tora convierte la experiencia negativa, el abuso del individuo débil, en algo totalmente positivo y constructivo para la nueva sociedad judía: empatía con los más vulnerables.

LA VERDADERA BONDAD CON LOS EXTRANJEROS

En esta misma Parashá, la Tora también transmite esta idea poderosa y revolucionaria en un contexto similar. El trato del “GUER”, es decir, el inmigrante que suele llegar sin familia a trabajar en otro país. Excepto en la nación judía, en la antigüedad estos trabajadores extranjeros no estaban protegidos por la ley local. Eran el epítome de la vulnerabilidad y, en general, sus amos abusaban de ellos. La Torá nuevamente nos sorprende: (Éxodo 23: 9): “No oprimas al extranjero, porque bien sabes lo que significa ser un extranjero, ya que fuisteis extranjeros en Egipto” El trauma del abusado – y su «inevitable» compulsión de abusar de otros – debe canalizarse de una manera diferente. La Torá nos enseña a “liberarnos” del círculo de abusados / abusadores, indicando que no estamos condenados al abuso. Y la mejor (o única) forma de romper el círculo del abuso consiste en comportarnos con más compasión con aquellos que están bajo nuestro poder. Siguiendo las instrucciones de la Torá, los ex esclavos judíos lograrán lo que aún hoy parece imposible: superar la necesidad psicológica de abusar de otros, para compensar el trauma de haber sido abusados en Egipto. Esta es también una forma de expresar «libertad», en este caso, la libertad psicológica que redime a una persona maltratada y rompe el círculo atroz del abusado / abusador.

La Ketubá, acta de matrimonio judío, establece las obligaciones del marido hacia su mujer (ver más aquí) Cuando el novio declara a su futura esposa que la está tomando legalmente como su esposa «de acuerdo con la ley de Moisés e Israel», el novio acepta todas las responsabilidades de un honorable marido judío.

En la Perashá de esta semana, Mishpatim, la Torá establece las tres obligaciones principales del marido hacia su esposa

1. she-erah: proporcionar a su esposa su sustento

2. kesutah: abastecer a su esposa de su ropa y su residencia

3. ‘onatah: convivir con ella.

1. Sheerah. La primera responsabilidad del marido es mantener a su esposa económicamente. Este es el primero de los 3 deberes establecidos por la Torá (Éxodo 21:10), que en el lenguaje de los rabinos se llama «mezonot» («comida», la pensión alimenticia).

Algunas ilustraciones de Maimónides sobre este punto, tomando en cuenta los usos y costumbres de la época del Talmud:

MT, Ishut 12:10-11: «El marido está obligado a suministrar comida a su esposa y a sus hijos de acuerdo a sus medios materiales. Una persona pobre solamente deberá proporcionar dos comidas basicas al día. Mientras que un marido en buena posición debe proveer a su mujer y familia alimentos nutritivos (carne, pescado, o lo que sea la costumbre local de las personas afluentes) todos los días.»

MT, Ishut 12:16-17: «Si el esposo se va de su casa por un viaje de negocios en el extranjero (en la antigüedad la gente viajaba al extranjero durante meses o años, y prácticamente no había ninguna posibilidad de comunicación. YB) y la esposa se queda sin medios materiales para obtener sus alimentos, la corte rabínica puede confiscar y vender las propiedades del marido, sin su consentimiento explícito, para proveer de alimentos a su esposa e hijos, con la condición que hayan pasado por lo menos tres meses desde que el marido salió de su casa. La corte rabínica asume en principio que cuando un marido judío responsable sale de viaje generalmente deja a su familia lo necesario para mantenerse por lo menos por 90 días.

2. Kesutah. Literalmente significa «su ropa, o su vestuario». El marido judío está obligado a proporcionar a su mujer la ropa adecuada, los muebles necesarios y un lugar de residencia.

Ilustraciones: Vestimenta: El marido tiene que suministrar a su mujer la ropa apropiada para cada estación del año. En cuanto a la calidad del vestuario , la regla es que el marido debe proveer a su esposa con un nivel de ropa de acuerdo con: a) lo que el marido puede permitirse, y b) la costumbre local. Por ejemplo, las necesidades sociales de una mujer que vive en el campo no son las mismas necesidades de una mujer que vive en la ciudad (Maimónides, MT ishut 13: 2). Esta categoría también incluye la obligación del marido de proporcionar a su esposa artículos que no son de primera necesidad (o superfluos), tales como joyas, cosméticos, etc., a un nivel que resulte del balance entre las posibilidades financieras del marido y las necesidades sociales de la esposa (13:4).

Lugar de residencia: El lugar de residencia a veces se registra por escrito en la Ketubá, si el marido y la mujer lo han acordado de antemano. Si el marido desea cambiar el lugar de residencia acordado, se espera que la esposa no se oponga. Algunas excepciones son: 1. Un barrio de mala reputación (13:15): la esposa puede negarse a trasladarse a una ciudad o un vecindario violento o corrupto. 2. Israel: si la pareja acordó vivir en Israel, la esposa puede negarse a salir de Israel; o si viven en Jerusalem, ella puede negarse a salir de Jerusalem. (13: 19-20). En este caso, no have falta ninguna otra razón de parte de la esposa para justificarlo.

3. ‘Onatah. En la Ley bíblica, se conceden de manera explícita los derechos conyugales a la esposa. La Torá indica en Éxodo 21:10 que el marido «no debe privar a su esposa de su comida, su ropa y sus derechos conyugales». En las palabras de Maimónides, un marido que priva a su mujer de intimidad, deliberada o maliciosamente, transgrede la obligación de ‘onatah, y es un causal válido de divorcio. Esto no se aplica, sin embargo, cuando por ejemplo, hay temas de salud de por medio. ( MT, ishut 14:7). El Talmud también analiza la frecuencia esperada de los deberes conyugales del marido, en base a su ocupación y trabajo (14: 1). También se espera que la esposa cumpla con sus deberes conyugales. Y una mujer que sin una razón justificada (kede letsa’aro) niega permanentemente a su marido de sus derechos conyugales, se considera una esposa rebelde (moredet) y pierde el derecho a la compensación establecida en la Ketubá en caso de divorcio (14: 9).

Es importante aclarar que el propósito principal de Mitsva de ‘ona es reforzar el vínculo de amor entre esposo y esposa, y que el esposo nunca deje de prestarle la atención debida a su esposa. En una Mitsvá separada, la Torá indica el mandamiento de tener hijos (perú urbú). Vale aclarar que la Mitsvá de ‘ona, intimidad (el eufemismo hebreo dice literalmente: “pasar tiempo con ella”) es independiente de la intención de procreación. Por lo tanto, incluso cuando la concepción no es posible –durante el embarazo o cuando la mujer está bajo tratamiento por control de la natalidad, o cuando la esposa ya no puede tener hijos– se espera que la pareja siga manteniendo una relación íntima activa.

FROM ENCYCLOPEDIA JUDAICA

The act of marriage creates certain rights and duties between husband and wife. In performing them, both parties have to conduct themselves according to the following rules, comprising the fundamental principles for the relationship between husband and wife in Jewish law: «Thus the sages laid down that a man shall honor his wife more than his own self and shall love her as he loves himself, and shall constantly seek to benefit her according to his means; that he shall not unduly impose his authority on her and shall speak gently with her; that he shall be neither sad nor irritable. Similarly they laid down that a wife shall honor her husband exceedingly and shall accept his authority and abide by his wishes in all her activities…» (Maim. Yad, Ishut 15:19–20).

A husband has ten obligations toward his wife (or her descendants) and four rights in respect of her. The obligations are (a) to provide her with sustenance or maintenance; (b) to supply her clothing and lodging; (c) to cohabit with her; (d) to provide the *ketubbah (i.e., the sum fixed for the wife by law); (e) to procure medical attention and care during her illness; (f) to ransom her if she be taken captive; (g) to provide suitable burial upon her death; (h) to provide for her support after his death and ensure her right to live in his house as long as she remains a widow; (i) to provide for the support of the daughters of the marriage from his estate after his death, until they become betrothed (see *Marriage) or reach the age of maturity; and (j) to provide that the sons of the marriage shall inherit their mother’s ketubbah, in addition to their rightful portion of the estate of their father shared with his sons by other wives. The husband’s rights are those entitling him: (a) to the benefit of his wife’s handiwork; (b) to her chance gains or finds; (c) to the usufruct of her property; and (d) to inherit her estate (Yad, Ishut 12:1–4; Sh. Ar., EH 69:1–3).

These rights and duties both derive from the law and not from mere agreement between the parties: «a man, by marrying a woman, becomes obligated to her in ten matters and acquires rights against her in four matters, even if they have not been taken down in writing» (Yad, Ishut 12:5; Sh. Ar., EH 69:1), i.e., the said rights and duties devolve as a matter of law from the act of marriage, whether or not a ketubbah deed is written and «writing thereof does not add and the absence thereof does not detract» (Resp. Ribash no. 480).

See *Maintenance.

This includes the right to household utensils and furniture and to a home of a reasonable standard in accordance with local custom (Yad, Ishut 13:3, 6; Sh. Ar., EH 73:1, 7). The scope of this right is governed by the rules pertaining to the law of maintenance, since, for the purpose of the legal rights of the wife, the concept of maintenance – in its wider meaning – embraces also the above-mentioned right (Tur, EH 73). By the same token the wife loses her right to claim raiment from her husband whenever she forfeits her right to maintenance (Rema, EH 69:4).

The place of residence (town or village) is determined by the husband, since it is presumed that they so agreed in advance and the wife cannot object to her husband changing their residence unless there was an agreement, express or implied, that they would not move to another place without her consent (Sh. Ar., EH 75:1; PDR 2:233, 3:161, 163, 5:20, 22, 57). However, the husband must have reasonable grounds for deciding on a change against the will of his wife, e.g., for reasons of health, or his livelihood, or the fact that the matrimonial peace at their existing home is disturbed by his or her relatives (Resp. Ribash nos. 81, 88; PDR 1:271, 274–5; 2:233, 237; 5:36, 54, 57). The wife is not obliged to agree to a change of residence if this should be detrimental to her position, e.g., because her relationship with her husband is such that she has reasonable grounds for her reluctance to move beyond the proximity of her relatives, or because the new home will be inferior to the old home, or if she can justify her refusal on the grounds that she does not wish to move from a town to a village or vice versa (Sh. Ar., EH 75:2; PDR 1, 2, loc. cit. 3:161, 163).

These rules do not apply in their entirety to Ereẓ Israel vis-à-vis other countries, nor to Jerusalem vis-à-vis other places in Ereẓ Israel. In such cases the rule is that a spouse who genuinely prefers as his place of residence Ereẓ Israel to any other country, or Jerusalem to any other place in Ereẓ Israel, need not bow to the wishes of the other spouse. In effect, therefore, the law favors the party genuinely seeking to settle in Ereẓ Israel or Jerusalem, or refusing to depart therefrom, even if, for example, this should entail the loss of better economic opportunities elsewhere, unless there is reason to fear that in Ereẓ Israel or in Jerusalem they might become in need of charity (Sh. Ar., EH 75:3, 4; Pitḥei Teshuvah, ibid., 6; PDR, 5:20, 36, 66). However, if settling in Ereẓ Israel involves any danger for the parties, neither spouse may compel the other to do so (Tos. to Ket. 110b, S.V. «hu Omer la’alot: Sh. Ar., EH 75:5; for a contrary opinion, cf. Tur, EH 75; see also PDR 5:20).

The husband likewise determines the place of the dwelling within the town or village, but each of the parties must comply with the other’s request to move to another dwelling and cannot refuse to do so on the ground that he or she is not particular about the matters complained of by the other spouse, provided only that the request is genuine and justified in the circumstances, e.g., on the grounds that neighbors are habitually insulting, or that they are given to prostitution, or to desecration of the Sabbath, and the like (Yad, Ishut 13:15; Sh. Ar., EH 74:11–12). If the wife refuses, in defiance of these rules, to accede to her husband’s just demands concerning their place of residence, she is liable to forfeit her right to maintenance since she is only entitled thereto as long as she lives with him; moreover she is likely to be considered a moredet (see below) and may eventually be obliged to accept a bill of *divorce (Sh. Ar., EH 75:4, PDR, 3:161, 163, 164; 5:20, 23–28; 6:5, 9). Similarly, upon the husband’s unreasonable refusal to accede to his wife’s just demand to continue living in Ereẓ Israel, he may be ordered to provide maintenance for her – even though they live apart – and eventually to grant her a divorce with payment of her ketubbah; and if necessary, she may also demand an injunction restraining him from going abroad (PDR 5:20, 24, 29, 36, 57–59, 66).

The husband’s duty to cohabit with his wife stems from biblical law (Ex. 21:10) and he is obliged to do so according to his physical abilities and in so far as it is possible for him, having regard to the requirements of his occupation (Yad, Ishut 14:1, 2; Sh. Ar., EH 76:1–3). If he is unable to fulfill this duty the wife is entitled to demand a divorce (Yad, Ishut 14:7; Sh. Ar., EH 76:11) unless there are reasonable prospects, on the strength of medical evidence, that he may be cured of his disability (PDR 1:85–89; 3:84–89; see also *Divorce).

Mored («rebellious» husband). A husband who refuses, without justifiable reason, to cohabit with his wife is called a mored (Ket. 63a; Yad, Ishut 14:15), but he is not so regarded if he refuses to fulfill his other obligations toward her (ibid. and Maggid Mishneh, Ishut 14:15; Baḥ, EH 77). Proof that her husband is a mored entitles the wife to demand that he be obliged to grant her a divorce, and if necessary, that he be compelled to do so (on the distinction, see *Divorce). As long as the husband persists in his refusal to cohabit with his wife, she is entitled to demand that the amount of her ketubbah be increased from week to week, as may be determined by the court and to receive the increased ketubbah upon the grant of the divorce (Ket., Yad, and Maggid Mishneh, ibid; Sh. Ar., EH 77:1). In such event the wife’s remedy is not necessarily limited to seeking a divorce – lest the husband be enabled thus indirectly to compel his wife to a divorce – she may alternatively demand that her husband be obliged to pay her maintenance only without prejudicing thereby her right to receive the increased ketubbah when later seeking a divorce (Sh. Ar., EH 77:1; Piskei ha-Rosh Ket. ch. 5:32). The husband will not be regarded as a mored when he can adduce facts in support of his plea that his wife is repulsive to him, and declares that he is ready and willing to give her a divorce forthwith, with payment of her ketubbah; the wife’s refusal to accept a divorce in such circumstances relieves the husband of all his obligations toward her, including that of maintenance (Resp. Rosh 42:1; PDR 5:292, 296, 297).

Moredet («rebellious» wife). The wife is similarly regarded as a moredet only when she persistently refuses to cohabit with her husband (Ket. 63a., Yad and Maggid Mishneh, Ishut 14:8; Sh. Ar., EH 77:2), but not when she refuses to fulfill any of her other marital duties (Sh. Ar., EH 77:2 and Baḥ EH 77). The moredet falls into two categories: firstly, that of a wife who refuses to cohabit with her husband because of anger or a quarrel or for other reasons offering no legal justification; secondly, that of a wife who refuses to cohabit with her husband because she cannot bring herself to have sexual relations with him and can satisfy the court that this is for genuine reasons, which impel her to seek a divorce – even with forfeiture of her ketubbah. In both cases the moredet immediately loses her right to maintenance (Sh. Ar., EH 77:2; PDR 6:33, 42) and, in consequence thereof, her husband loses the right to her handiwork (see below) since he is only entitled to this in consideration of her maintenance, i.e., only if she is actually maintained by him (Rema, EH 77:2; and see below). Ultimately, the moredet also stands to lose her ketubbah and the husband will be entitled to demand a divorce, but this depends on conditions that differ according to the category of moredet and in this regard the halakhah underwent various developments.

So far as the first category of moredet is concerned, it was laid down in the Mishnah that her ketubbah shall be diminished from week to week until nothing remains and that thereafter her husband shall be entitled to divorce her without ketubbah (Ket. 63a). Later, as a means of inducing the wife to desist from her «rebellion,» it was provided that a procedure be adopted of having certain warnings issued by the court as well as public announcements made, and, on the wife’s disregarding a final warning that her continued «rebellion» would render her liable to forfeiture of her ketubbah, the court could declare her a moredet, entailing the immediate forfeiture of her ketubbah and the acquisition by her husband of the right to divorce her forthwith. In the period of the later amoraim it was further prescribed that only after persisting in her refusal to cohabit with her husband for not less than 12 months would the moredet finally lose her ketubbah and the husband become entitled to divorce her (Ket. 63b; Yad, Ishut 14:9–11; Tur and Beit Yosef, EH 77; Sh. Ar., EH 77:2). This appears to be the halakhah at the present time (see PDR 6:33, 325).

In the case of the other category of moredet (i.e., on a plea of incompatibility, when accepted by the court), the procedure of warnings and announcements was regarded as being inappropriate and inapplicable since «the wife should not be urged to have sexual relations with a person whom she finds repulsive» (Yad, Ishut 14:8; PDR 6:5, 12, 18). Hence, in this case, the husband was at first considered entitled, according to her own wish, to give his wife an immediate divorce, without payment of her ketubbah, because she herself had desired this by her waiver of the ketubbah and, as a moredet, she is anyhow not entitled to her ketubbah (Ket. 63b: Sh. Ar., EH 77:2). In later times, however, the scholars regulated that even concerning this category of moredet the husband is not entitled to divorce her immediately, but only after the lapse of 12 months after a warning by the court that she might forfeit her ketubbah. This regulation aimed at enabling the wife to reconsider her attitude in the event that her rebelliousness had been due to sudden anger which she later regretted (Ket. 63b). Her failure to repent within those 12 months would then entitle the husband to divorce her without ketubbah but the wife’s plea that her husband is «repulsive» to her does not give her the right to demand that her husband be adjudged to grant her a divorce. Maimonides’ opinion (Ishut 14:8) that on the strength of the aforesaid plea, the husband might even be compelled to divorce his wife without delay – since «she is not like a captive to have to submit to intercourse with someone repulsive to her» – was not accepted by the majority of the authorities and a takkanah to a similar effect from the geonic period (knownas the dina de-metivta, i.e., «law of the academies») was regarded as an emergency measure intended only for those generations and not as established halakhah (Resp. Rosh no. 43:6, 8; Sefer Teshuvot ha-Rashba ha-Meyuḥasot le-ha-Rambanno. 138; Rema EH 77:2, 3).

Since the wife only forfeits her ketubbah in the event that she does not desist from her rebellion within the prescribed period of 12 months, all her rights and duties on the strength of the ketubbah – save with regard to her maintenance and her handiwork – remain valid during the same period, since «the ketubbah conditions are as the ketubbah itself.» If in consequence of the wife’s rebellion she is divorced by her husband, she will anyway be entitled to receive her nikhsei melog (property which never ceases to remain in her ownership but the usufruct whereof is enjoyed by the husband (see *Dowry) but special halakhot exist concerning her nikhsei ẓon u-varzel (see Beit Shemu’el and Ḥelkat Meḥokek at concl. of 77).

See *Ketubbah.

The medical expenses incurred in case of the wife’s illness must be borne by her husband, since these form part of her maintenance: «medical care in time of illness is as necessary to a person as is sustenance» (Ket. 4:9 and Rashi Ket. 51a S.V. «ḥayyav lerape’ot«). Hence, questions such as the scope of this obligation of the husband and whether and to what extent he is obliged to defray debts incurred by the wife in seeking a cure for her illness are governed by the same laws as those pertaining to her maintenance.

The husband is obliged to provide the money and to perform any other act required to redeem his wife from captivity (Ket. 4:9 and 52a; Sh. Ar., EH 78:1). «Captivity» in this context is not confined to the case of actual captivity of the wife in time of war, but embraces all circumstances in which she is prevented, as a result of the restriction of her freedom, from living with her husband, e.g., where husband and wife are separated as a result of persecution or war and thereafter the husband succeeds in reaching Ereẓ Israel while his wife is stranded in a country from which she is not free to depart. If in such circumstances the payment of money will enable the wife to leave that country and join her husband, it is his duty to pay the required amount, even if it should exceed the amount of her ketubbah, because in general the husband’s duty is to ransom his wife with all the means at his disposal: «his wife is as his own self » (Yad, Ishut 14:19; Rema EH 78:2; Ha-Gra, EH 78, n. 4). In consideration of this duty the husband is entitled to the usufruct of his wife’s property. The husband cannot be relieved of this duty by his wife’s waiver of her right to be ransomed – even if the parties should so agree prior to their marriage – lest she become assimilated among the gentiles (Sh. Ar., EH 69:5).

It is the husband’s duty to bear the costs of his wife’s burial and all related expenses such as those necessary for erecting a tombstone, etc. (Sh. Ar., EH 89:1). Since this duty is imposed on the husband as one of the ketubbah conditions and not by virtue of the laws of succession, he must bear these costs out of his personal property without regard to the question whether, and to what extent, his deceased wife had contributed a dowry or left an estate in his favor (Beit Shemu’el 89, n. 1). If such burial costs are defrayed by third parties, e.g. by the ḥevra kaddisha, in fulfilling the mitzvah of burying the dead, in the husband’s absence or upon his own refusal to do so, the husband will be liable to refund the amount expended to the parties concerned (Sh. Ar., EH 89:2).

See *Widow.

See *Parent and Child (Legal Aspects).

INHERITANCE BY THE SONS OF THE MARRIAGE OF THEIR MOTHER’S KETUBBAH, OVER AND ABOVE THEIR PORTION IN THE ESTATE OF THEIR FATHER

This takkanah, known as the ketubbat benin dikhrin (i.e., ketubbah of male children), refers to a condition of the ketubbah whereby the husband agrees that his wife’s ketubbah and dowry, which he – as by law he is her only heir (see *Succession; and see Right of Inheritance, below) – would inherit if she predeceased him, shall, upon his own death, pass to the sons of the marriage only and this over and above and separately from the share of these sons in the rest of their father’s estate shared equally by them with the sons of any other marriage contracted by him (Ket. 4:10 and 52b; Sh. Ar., EH 111). This takkanah, designed to ensure that the wife’s property would remain for her sons only, was aimed at influencing the bride’s father to give her, upon her marriage, a share of his property equaling that which his sons would get; however, since it anyway became customary for fathers to give their daughters such a share of their property, the need for including a specific undertaking of this kind in the ketubbah-deed fell away, and therefore by geonic times it was already recognized that the takkanah had become obsolete (Rema, EH 111:16).

(«the wife’s handiwork»). It is the wife’s duty to do all such household work as is normally performed by women enjoying a standard of living and social standing similar to that of the spouse all in accordance with local custom. Also applicable is the rule that «the wife goes up with him, but does not go down with him,» i.e., she is not obliged to do the kind of work that was not customarily done by the woman in her family circle prior to her marriage, although according to the husband’s standard women used to do it, while at the same time she is entitled to benefit from the fact that her husband enjoys a higher standard of living than that to which she was accustomed prior to the marriage, so that she is not obliged to do work which is not normally done by women enjoying the husband’s (higher) standard of living even if she used to do it prior to her marriage (Ket. 59a–61b; Sh. Ar., EH 80:1, 10). The expenses incurred by the husband in hiring domestic help due to the fact that the wife, although able to perform them, willfully refuses to perform the duties devolving on her, as described, must be refunded by the wife and may also be deducted by the husband from her maintenance (Sh. Ar. ibid; Ḥelkat Meḥokekn. 80, 27). According to these rules, the question must also be decided as to whether, and to what extent, the wife is obliged to suckle or look after the infant children of the marriage, since this duty is imposed on her not as the mother of the children but as the wife of their father (Sh. Ar., EH 80:6–8). Hence a divorced woman is exempt from this duty, with the result that her former husband – who as father always bears sole responsibility for the maintenance of their children (see Parent and *Child) – must compensate her for her efforts, if she nevertheless looks after them, in addition to bearing the expenses involved (Sh. Ar., EH 82:5; PDR, 1:118, 119; 2:3–8).

The wife is not liable for damage caused by her in the home – e.g., in respect of broken utensils – whether or not occasioned in the course of fulfillment of her duties (Yad, Ishut 21:9, Sh. Ar., EH 80:17 and Ḥelkat Meḥokek 80 n. 29). The purpose of this halakhah is to preserve matrimonial harmony, since otherwise «matrimonial harmony will cease, because the wife in taking excessive care will refrain from most of her duties and quarreling will result» (Yad, loc. cit.).

The question whether the earnings of the wife from her own exertions (yegi’a kappeha), in talmudic language ha’adafah («surplus»), and, if she exerts herself more than usual, «surplus resulting from undue exertion,» are in the nature of ma’aseh yadeha and so belong to her husband, is a disputed one – both in the Talmud (Ket. 65b and Rashi thereto S.V. ha’adafah; 66a) and in the codes (Yad, Ishut 21:2 and Sh. Ar., EH 80:1 as against the Tur, ibid., and other codes; PDR, 1:81, 90–94). In the light of this dispute the husband has no right to demand that his wife should go out to earn, nor that she should make over any such earnings to him; on the other hand, since some of the authorities are of the opinion that the husband does have this right – thus possibly entitling him to set off such earnings against her maintenance – he will not be ordered to pay her maintenance in so far as her earnings suffice for this purpose (see Kim Li; Baḥ EH 80; PDR, 1:94, 118; 2:220, 226).

The husband’s right to his wife’s handiwork is granted to him in return for his duty to maintain her and in consideration of this, and is only available to him upon his actually discharging this duty (Ket. 47b, 58b, 107b; Sh. Ar., EH 69:4). The rule is that the wife’s right to maintenance is primary, taking precedence over his right to her handiwork and existing even when she is unable to work, e.g., on account of illness (Ket. 58b; Rashi ad loc. S.V. mezonei ikkar). On the other hand, the husband loses the right to his wife’s handiwork if for any reason whatsoever she does not actually receive her maintenance from him, whether on account of his refusal to provide it or because according to law she has forfeited her right to such maintenance, e.g., because she is a moredet (Rema EH 77; 2; Ba’er Heitev, EH 80, n. 1). On the strength of the above rule, the wife, by her independent will, is able, by waiving the right of maintenance, to deprive her husband of his right to her handiwork («I am not maintained, nor shall I do any handiwork…» Ket. 58b), a worthwhile step for her if she should earn more than the amount of her maintenance. The husband, on the other hand, cannot deprive his wife of her right to maintenance by waiving his right to her handiwork, nor may he demand that she go out to earn the cost of her maintenance («Spend your handiwork for your maintenance,» Ket. 58b; Sh. Ar., EH 69:4; Beit Shemu’el 69, n. 4).

The husband is entitled to the finds or chance gains of his wife (Ket. 65b–66a; Sh. Ar., EH 84).

See *Dowry.

Jewish law decrees that the husband is the sole heir of his wife – to the absolute exclusion of everyone else, including her children – as regards all property of whatever kind in her estate, including the part in respect whereof he had no usufruct during her lifetime. However, the wife is not an heir to her husband’s estate (BB 8:1 and 111b; Yad, Naḥalot 1:8; Ishut 22:1; Sh. Ar., EH 90:1); instead she has the right to claim maintenance and lodging from his estate for as long as she remains a widow. The husband inherits only the property actually owned by his wife at her death but not the property which is only contingently then due to her in certain circumstances, e.g., if she had been a contingent heir to her father but predeceased him (BB 113a; Sh. Ar., loc. cit.). The inheritance of the husband also embraces property sold by the wife subsequent to their marriage, since his right of inheritance comes into existence upon their marriage and therefore any sale of her property is only valid to the extent that it is not prejudicial to his right, i.e., only if he should predecease her or if they become divorced and she retains ownership of her property (Maim. Yad, Ishut 22:7; Sh. Ar., EH 90:9; see also *Dowry). The husband’s right to inherit his wife’s estate is co-extensive with the existence of a valid marriage between them at the time of her death, and remains effective even if the marriage between them was prohibited, e.g., between a priest and a divorcee (see Marriage, *Prohibited), and even if the husband had wished to divorce his wife but was prevented from doing so, whether for lack of time or on account of the decree of Rabbenu Gershom (see *Divorce; Main. Yad, Nahalot 1:8; Ishut 22:4; Sh. Ar., EH 90:1; Ba’er Heitev, ibid., n. 1).

All the above-mentioned rights and duties of the parties flow from the law. There is, however, no obstacle to an agreement between the parties to regulate their legal relationship with regard to monetary matters to another effect, provided that this is not in conflict with any general principles of the halakhah.

The rule is that «in a matter of mamon one’s stipulation is valid,» i.e., in matters of civil law the law does not restrict the freedom of contract and one may even stipulate contrary to biblical law (R. Judah, Kid. 19b; Sh. Ar., EH 38:5; 69:6). Hence the parties may come to an agreement stipulating therein terms and conditions whereby they forego certain pecuniary rights and obligations they are entitled to against each other according to law, provided that the agreement is express and in compliance with the legal provisions concerning the making of such an agreement or condition. In particular, and by way of an express agreement for the renunciation (silluk) of their rights, a husband and wife may effect a complete separation of their rights as to their respective properties so as to deprive the husband of the usufruct of his wife’s property and of the right to inherit from her. It should be noted that such an agreement will lack validity prior to the creation of any legal tie between the parties with reference to the rights in question, because until then such rights constitute «something that is not yet in existence» (davar she-lo ba la-olam; see *Contract) and therefore cannot be the subject of a legal disposition; nor is such an agreement possible after full acquisition of the said rights, since a right once acquired cannot be conferred on another by renunciation but only by way of its transfer or assignment. Hence the above-mentioned renunciation agreement must be effected after the kiddushin but prior to the nissu’in ceremony (see *Marriage), since at this stage the pecuniary rights are considered already to be «something in existence» but they are not yet fully acquired by the parties (see PDR I, 289–313; Beit Ya’akov, EH 92:7). Since the custom at the present time is for the kiddushin and nissu’in ceremonies to be united and performed one after the other without interruption, it is necessary, if the parties should wish to effect the said renunciation, that the marriage ceremony be interrupted upon completion of the kiddushin to enable the parties to sign the renunciation deed, and then only to proceed with the nissu’in ceremony.

As said above, only with regard to monetary matters is such an agreement valid. Therefore, an agreement whereby the wife undertakes to waive her right to cohabitation is of no effect since the corresponding duty of the husband is imposed on him by biblical law and does not involve a matter of mamon; hence the wife may always repudiate such an agreement and demand that her husband fulfill his duty to cohabit with her (Yad, Ishut 12:2, 7; Sh. Ar., EH 69:6, Ḥelkat Meḥokek 69, n. 10). On the other hand, the wife’s duty to cohabit with her husband is not imposed on her by biblical law as such, but is merely a consequence of the husband’s right to cohabitation by virtue of the marriage, which right he may waive. Hence an agreement between the spouses whereby the wife is released from this duty but without any waiver of her rights is valid, and she will not be considered a moredet if, in reliance upon such agreement, she should refuse to cohabit with her husband; neither will her right to maintenance and other pecuniary rights be affected (Pitḥei Teshuvah, EH 134, n. 9).

Also invalid is a condition depriving the wife of her «main» ketubbah – even though her right to the ketubbah is a matter of mamon – since a marital life in which the wife remains without her «main» ketubbah is considered «cohabitation for the sake of prostitution» (Ket. 5:1) and «it is forbidden for a man to remain with his wife for even one hour if she has no ketubbah» (Yad, Ishut 10:10). Depriving the wife of her «main» ketubbah, or the diminution thereof below the statutory minimum, is prejudicial to the very existence of the marriage and cohabitation in such circumstances is considered as tantamount to prostitution; hence a condition of this kind relates to davar she-be-issur (a matter of a ritual law prohibition) and not to a davar she-be-mamon, and accordingly it is invalid (Yad, Ishut 12:8; Sh. Ar., EH 69:6).

The husband’s right to inherit from his wife, which flows from the law upon the celebration of the marriage, likewise cannot be stipulated away during the subsistence of the marriage. Upon the celebration of the marriage the husband forthwith acquires the status of heir designate to his wife’s estate and although this is calculated eventually to afford the husband rights of a monetary (mamon) nature it creates a legal status and as such cannot be the subject matter of a waiver of stipulation aimed at annulling it (Yad, Ishut 12:9; Sh. Ar., ibid.). Any such waiver or stipulation, in order to be valid, has therefore to be effected after kiddushin and prior to nissu’in (Yad, Ishut 23:5–7, and Maggid Mishneh thereto; Sh. Ar., EH 69:5, 7; 92:7, 8). For further particulars concerning freedom of stipulation between husband and wife, see *Contract.

The halakhah is generally followed so far as the particulars of the marital rights and duties are concerned. However, the husband’s right to inherit from his wife is governed by the Succession Law, 5725 – 1965, in terms whereof – as also formerly in terms of the Succession Ordinance, 1923–34 – one spouse inherits from the other along with the latter’s descendants (in the case of intestate succession), in the prescribed proportions (sec. 11). The inheritance rights of the spouses are governed solely by the provisions of the above law and the rabbinical courts must also adjudicate in accordance therewith, save when all the interested parties agree, in writing, to the jurisdiction of the rabbinical court and provided that the rights of a minor or a person lacking legal capacity who is party to the estate shall not be less than those afforded him under the above law (sec. 148, 155).

I.S. Zuri, Mishpat ha-Talmud, 2 (1921), 79–87; Gulak, Yesodei, 1 (1922), 36f.; 4 (1922), 53, 59 n. 1, 116, 144; Gulak, Oẓar, 23–25, 53f., 59–67; A. Gulak, in: Ha-Mishpat ha-Ivri, 2 (1926/27), 266; idem, in: Zeitschrift fuer vergleichende Rechtswissenschaft, 47 (1932/33), 241–55; J. Epstein, in: Ha-Mishpat ha-Ivri, 4 (1932/33), 125–34; S. Eliezri, in: Sinai, Sefer Yovel (1958), 338–43; ET, 1 (19513), 224–6; 4 (1952), 69–78, 80–88, 91–95; 7 (1956), 61–63; Z. Warhaftig, in: Divrei ha-Congress ha-Olami ha-Revi’i le-Madda’ei ha-Yahadut, 1 (1967), 189–94; abstract in Engl.: ibid., Eng. Sect., 267f.; B. Schereshewsky, Dinei Mishpaḥah (19934), 97–146, 171–215; M. Elon, Ḥakikah Datit… (1967), 42–44, 161, 167–9; idem in: ILR, 4 (1969), 134f., 137. ADD. BIBLIOGRAPHY: M. Elon, Ha-Mishpat ha-Ivri (1988), 1:110, 112, 188, 465ff., 468, 469, 472ff., 516, 537, 538ff., 541ff., 635, 637, 653, 671, 677ff., 681, 683; 3:1339, 1499ff., 1526ff.; idem, Jewish Law (1994), 1:124, 126, 211; 2:568, 571, 572, 575ff., 628, 654, 655ff., 658ff., 787, 789, 808, 828ff., 835ff., 840, 842ff.; 4:1599, 1785ff, 1816ff.; M. Elon and B. Lifshitz, Mafte’aḥ ha-She’elot ve-ha-Teshuvot shel Ḥakhmei Sefarad u-ẓefon Afrikah (legal digest) (1986) 1:36–47, 170–73; B. Lifshitz and E. Shochetman, Mafte’aḥ ha-She’elot ve-ha-Teshuvot shel Ḥakhmei Ashkenaz, Ẓarefat ve-Italyah (legal digest) (1997), 28–33, 111–114; A. Rosen-Tzvi, Dinei ha-Mishpaḥah bein Kodesh le-Ḥol (1990), 297, 419, 422; A. Westereich, «Aliyata u-Sḥehikatah shel Illat ha-Moredet,» in: Shenaton ha-Mishpat ha-Ivri, vol. 21, 123.

Sources: Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2007 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved.

Este acuerdo para la liberación de rehenes, que al momento que escribo estas líneas aún no ha sido firmado, parece un muy mal acuerdo: para comenzar, no se negocia con terroristas. A los terroristas hay que jugarles su juego. En hebreo se dice: Haba lehorgueja, hashkem le’horgo. Cuando alguien tiene la intención de matarte —y en el caso de Hamas, esa intención está explícita en su carta fundacional—, mátalo primero.

En mi opinión, en lugar de negociar, Israel debería comenzar por debilitar a Hamas. ¿Cómo? Cortando la ayuda humanitaria a Gaza, los cientos de camiones con comida y gasolina que entran cada día a Gaza mantienen vivo y poderosos a Hamas.

Luego, Israel debería usar su fuerza militar para liberar a los rehenes . Aunque es arriesgado y puede costar vidas. Porque estadísticamente se perderán muchas más vidas liberando a terroristas asesinos de Hamas. Ya vimos que, como consecuencia directa o indirecta de la liberación del soldado Guilad Shalit, 1027 terroristas fueron liberados, el 80% de ellos volvieron a cometer actos de terror y como consecuencia MILES de israelíes fueron asesinados. Incluyendo las víctimas del 7 de octubre, ya que el que organizó ese ataque fue Sinwar, uno de los liberados en el intercambio por Shalit.

Israel debe proteger su reputación. Hasta la semana pasada Israel era considerado el gran triunfador en el Medio Oriente lo cual le concede un nombre con un gran poder de persuasión. Y en el Medio Oriente, TODO es cuestión de reputación. Cuando los vecinos ven fuerza, coraje y triunfo, te respetan y no se meten contigo. Pero cuando ven debilidad —y este acuerdo refleja mucha debilidad—, allí se envalentonan y te atacan por todos los frentes.

Negociar con Hamas para liberar a los rehenes envía un claro y terrible mensaje que los enemigos de Israel entienden muy bien: si quieres destruir a Israel, dañarlo internamente, hacerlo sangrar y hasta obtener cualquier concesión del Estado judío todo lo que tienes que hacer es secuestrar a un judío. Para mayor beneficio: a una madre con dos pequeños hijitos. Israel te va a dar todo para liberarlos. Negociar por rehenes es la mejor formula para estimular al enemigo a aumentar su sed de secuestros extorsivos. Liberar a los terrosas seisenos, es la mejor manera de estimular mas actos de terrorismo ya que los criminales saben que en poco tiempo, luego de algún secuestro exitoso, podrán salir libres.

Estos son los riesgos y los puntos mas dañinos de este “acuerdo”.

Por otro lado, no puedo concebir que Netanyahu no sabe todo esto. O no lo Ema en cuenta. El primer ministro de Israel ha demostrado ser extraordinariamente inteligente y FIRME cuando se trata de la seguridad de Israel, lo cual quedó claro en todas las veces que desde que comenzó la guerra se enfrentó a su mayor aliado, Estados Unidos. En una entrevista que recuerdo claramente, le preguntaron a Netanyahu cómo quería ser recordado, y él dijo: «Como quien aseguró el bitajón (la seguridad) de Medinat Israel». Me resulta inconcebible pensar que Netanyahu simplemente “haya cedido” a la presión de Biden para hacer un acuerdo tan desfavorable, especialmente cuando faltan solo 4 días para que asuma el nuevo gobierno .

Paso ahora a especular sobre algunas de las cosas que pueden haber ocurrido para que este acuerdo se lleve a cabo:

Una posibilidad es que Biden, Blinken y Sullivan quisieran que esta operación salga adelante para llevarse el crédito de haber liberado a los rehenes y que la administración tenga un legado del cual jactarse o para seguir adelante con la doctrina anti israelí de Obama. Y para lograr esto hayan amenazado a Israel con que si no aceptan un acuerdo con Hamas, Estados Unidos podría NO utilizar su veto en la ONU. Explico: el arma más poderosa que tiene Estados Unidos sobre Israel es su veto en las Naciones Unidas. Cada vez que las Naciones Unidas intentan exigirle a Israel alguna concesión, que en teoría obliga a todos los estados miembros, Estados Unidos impone su veto. Imaginemos, por ejemplo, que Francia e Inglaterra deciden exigir en el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU que, bajo amenaza de sanciones internacionales, Israel se debe retirar de los territorios reconquistados en el Golán sirio o de la franja de seguridad en el Líbano, lo cual ha sido la mayor victoria de Israel en esta guerra. Sería un problema eterno para Israel en los años o décadas que vienen, porque incluso si Trump intentara revertir ese decreto, otros países como Rusia y China lo bloquearían con su veto. El daño que en estos 4 próximas días Estados Unidos puede causarle a Israel no usando su veto—sería irreversible. (Quizás Netanyahu juegue con el tiempo, y no se firme el acuerdo hasta el 20 de Enero, hasta que pase el peligro…).

Otra posibilidad. Netanyahu esté seguro de que Hamas violará el alto al fuego, lo que daría a Israel todas las razones para regresar a Gaza con el apoyo de Estados Unidos sin deberle nada a Hamas por los rehenes liberados.

Otra posible escenario es que, para iniciar su gobierno con un triunfo diplomático impresionante y poder dedicarse de lleno no a Hamas, sino a sus problemas domésticos, Trump haya prometido a Israel a cambio de esta concesión enormes beneficios a largo plazo, como acompañar a Israel en un ataque a Irán, proporcionar todas las armas necesarias, ampliar los Acuerdos de Abraham con Arabia Saudita, forzar a Egipto a abrir las fronteras de Gaza para que los gazatíes salgan, y apoyar la captura o eliminación de los terroristas liberados. Que la verdad sea dicha: a esta altura todos conocemos los detalles del posible acuerdo entre Israel y Hamas, pero nadie sabe en absoluto los detalles del acuerdo entre Netanyahu y Trump. Y esta parece ser la clave de todo este asunto.

Repito, todo esto es pura especulación basada en el hecho de que Netanyahu ha demostrado ser un líder muy inteligente y cuidadoso, especialmente después del 7 de octubre.

Mientras tanto, rezo a Bore Olam para que proteja a nuestros soldados, y especialmente que inspire a nuestros líderes y les dé la inteligencia y la sabiduría para tomar las mejores decisiones para Am Israel.

Confío en que así será.

Parashat Vayijí (ויחי) que significa “Y vivió…” , alude a los últimos 17 años de la vida del patriarca Jacob en Egipto.

1. LOS ULTIMOS DIAS DE JACOB

Cuando Jacob siente que su vida está llegando a su fin, llama a Yosef y le hace prometer que lo enterrará en Israel, y no en Egipto. Yosef accede a la solicitud de su padre. Cuando Jacob se enferma y cae en cama Yosef lo visita, acompañado de sus dos hijos Menashé y Efraim. Jacob le concede a Efraim y Menashé el estatus de “jefes tribales”, es decir, que Yosef, en lugar de heredar una sola tribu como sus hermanos heredará el doble: tendrá dos tribus, Menashé y Efraim, en lugar de una sola que se hubiese llamado “Yosef”. Yosef le pide a su padre que bendiga a sus hijos. Jacob cruza sus manos y posa su mano derecha, con la que se consagraba al primogénito, sobre la cabeza de Efraim, el menor de los dos hermanos. Y los bendice diciéndoles: «Que el ángel de haShem que me redimió de todo mal bendiga a los jóvenes, y que sean llamados por mi nombre y por el nombre de mis padres, Abraham e Isaac, y que se multipliquen en abundancia en toda la tierra.» Yosef se inquieta porque piensa que Jacob puso su mano derecha sobre Efraim por error, e intenta colocar la mano de su padre sobre Menashé. Pero Jacob se niega y le dice que él sabe quién es el hijo mayor, pero “el hermano menor será mayor, y sus hijos se llenarán de fama en las naciones». Luego Jacob los bendice diciendo que el pueblo de Israel bendecirá el uno al otro diciendo: «Que Dios te bendiga como a Efraim y Menashé».

2. LA BENDICION FINAL DE JACOB

Luego Jacob convoca a todos sus hijos y le dedica un mensaje o una bendición personalizada, según el carácter, los talentos, el futuro y el potencial de cada uno de ellos. Reubén es criticado por su impulsividad y por haber profanado la cama de su padre. Shimón y Levi también son reprendidos por su ira, que se expresó en la matanza de los hombres de Shejem. Yehudá es bendecido con la monarquía y el éxito en la batalla. Zebulún es bendecido por sus talentos en el comercio marítimo. Jacob compara a Isajar con un fuerte burro (el burro era un animal respetado en esos días) que trabaja sin descanso. Dan posee la habilidad de juzgar. Gad, valentía en la batalla. Asher , la capacidad de producir abundante aceite y comercializarlo. Naftalí, posee la velocidad de los ciervos. Yosef es reconocido por su encanto, su sufrimiento y su rectitud y recibe una gran variedad de bendiciones. Benjamín, finalmente, es comparado con un lobo feroz que enfrenta sin miedo a sus enemigos. Jacob también reitera ante todos sus hijos su solicitud de ser enterrado en Israel, en la Cueva de Majpelá en Hebrón. Luego de bendecir a sus hijos fallece con una edad de 147 años.

3. EL FUNERAL

Después de un período muy prolongado de duelo nacional donde todo Egipto llora por al muerte de Jacob, Yosef recibe el permiso del Faraón para trasladar el cuerpo de Jacob a Israel. Una gran procesión fúnebre compuesta por todos los ancianos de Egipto y toda la familia de Jacob se traslada a Israel para enterrar a Jacob.

4. LA FAMILIA NUEVAMENTE UNIDA

Luego, ya de regreso en Egipto, los hermanos de Yosef temen que ahora, una vez que Jacob ya no está vivo, Yosef se vaya a vengar de ellos por haberlo vendido como esclavo. Pero Yosef les asegura que no les guarda rencor. La familia de Israel finalmente vuelve a estar unida y en paz.

5. EL ULTIMO DESEO DE YOSEF

Yosef vive hasta la edad de 110 años. Antes de fallecer, le dice a sus hermanos que Dios eventualmente los sacará de Egipto y los devolverá a la Tierra de Israel. Yosef les hace prometer que cuando llegue ese momento sus restos mortales sean llevados con ellos para ser enterrados en la tierra de Israel, como hizo su padre.

Cuando nuestro patriarca Ya’aqob se aprestaba a descender a Egipto y reunirse con su hijo Yosef —el segundo hombre más poderoso de Egipto— tuvo miedo. Y dudas. HaShem se reveló a Ya’aqob y le dijo: “No tengas miedo de descender a Egipto, Ya’aqob, allí haré de ti una gran nación”. ¿Cuál era el temor de Ya’aqob?

PREVENIR ANTES QUE CURAR

Nuestro patriarca temía que sus nietos y sus bisnietos se asimilasen a la cultura egipcia, y terminaran siendo “egipcios de origen semita”. La asimilación de los inmigrantes a la tierra que los acoge no solo es común, sino normal y en cierta manera, deseable. En Estado Unidos hay nietos y bisnietos de inmigrantes italianos, irlandeses o polacos, que llegaron aquí al principio del siglo XX (o antes!) y hoy se consideran a sí mismos 100% americanos. No tienen, que yo sepa, ninguna conexión “existencial” con la antigua tierra de sus antepasados o su cultura, excepto quizás en temas culinarios. Este era el miedo de Ya’aqob. Que sus descendientes se asimilen.Ya’aqob hizo dos cosas para prevenir la asimilación. En primer lugar, según nuestros Sabios, Ya’aqob envió a Yehuda antes de que llegará la familia y le encomendó organizar un Talmud Torá, una escuela judía. De esta manera, podrían seguir inculcando a sus hijos los valores de Abraham Abinu. En segundo lugar, Yaaqob le pidió a Yosef que al morir llevase su cuerpo a la tierra de Israel. De esta manera, los nietos y bisnietos de Ya’aqob tendrían siempre presente que su lugar definitivo está en Israel.

YOSEF SE UNE AL ESFUERZO

Yosef, por su parte, también tomó varias medidas para evitar la asimilación. En primer lugar, estableció a su familia en la tierra de Goshen, una tierra apartada. Y le dejo claro al Faraón, y a su propia familia, que seguirían dedicándose a la ganadería, un trabajo que estaba prohibido para los egipcios, por sus convicciones religiosas (creían que los animales encarnaban el espíritu de sus dioses y sus muertos). De esta manera, Yosef quería que su familia mantuviera una relación social limitada con los Egipcios. y con códigos religiosos diferentes. En tercer lugar, Yosef, tal como lo hiciera su padre, hizo jurar a sus descendientes que su cuerpo también tenía que ser sacado de Egipto y llevado a la tierra de Israel.

APARIENCIA, NOMBRES Y LENGUAJE

Y hay más. En el aspecto social los judíos rehusaron adoptar ciertos elementos de la sociedad egipcia. Los hijos y descendientes de Israel mantuvieron la vestimenta tradicional semita, y no adoptaron la vestimenta egipcia. Dicho se de paso, si bien creo que no tenemos muchos detalles de cómo era esa vestimenta judía, muy probablemente en los hombres se trataba de una barba corta y túnicas especiales. La imagen que vemos arriba muestra una familia semita (los egipcios no eran semitas) que llegaba de Canaan y se ve claramente la diferencia con los egipcios en estos dos elementos. La forma de vestir de los descendientes de Ya’aqob era lo suficientemente significativa para distinguir visualmente al judío del no judío. Nuestros Sabios también explican que los Yehudim no cambiaron sus nombres hebreos por nombres egipcios. Así, aunque el judío no estuviera presente, cuando alguien mencionaba a “Levi” o “Shimón” sabían que se estaban refiriendo a un individuo judío. Finalmente, tampoco cambiaron su lenguaje. Esto quiere decir que los padres hablaban en sus casa hebreo con sus hijos, posiblemente en las escuelas se enseñaba en hebreo y puede ser también (es solo una sugerencia de mi parte, sin mucha evidencia…) que si su lengua materna era el hebreo, cuando hablaban egipcio lo hacían con “acento hebreo”.

EGIPTO, VISTO DESDE CHINA

Respecto al origen de estos 3 elementos, mi hijo David, que es Rab en la sinagoga Sefaradí de la ciudad de Shanghai (China) compartió conmigo su Jiddush (=interpretación creativa). Me dijo que estos 3 elementos fueron los mismo que la Torá menciona respecto a Yosef, cuando a la fuerza tuvo que asimilarse al mundo egipcio. Cuando Yosef sale de la cárcel, lo rasuran y lo visten como un egipcio. Luego, cambian el nombre de “Yosef” por un nombre egipcio, “Tsafnat Pa’aneaj” (el descifrador de lo oculto). Y finalmente, también vemos que Yosef adopta el lenguaje egipcio como su primera lengua, ya que cuando se comunicaba con sus hermanos, antes de darse a conocer, lo hacía a través de un traductor. No creo que sea casualidad que estos mismo tres elementos hayan sido identificados por nuestros Sabios (¡o quizás por el mismo Yosef!) como los elementos que llevan o aceleran la asimilación de un grupo humano a su nuevo entorno.

APRENDIENDO DEL PASADO

Para resumir, para luchar contra la asimilación, en su nuevo lugar de residencia los descendientes de Ya’aqob tenían su propio sistema de educación judía; mantenían una conexión de identidad muy fuerte con la tierra de Israel; vivían en comunidad; trabajaban en una industria en la cual los egipcios no participaban; su apariencia era judía; sus nombres eran hebreos y hablaban en hebreo.

(Continuará….)

Cuando nuestro patriarca Ya’aqob luchó con un ángel y lo derrotó, el ángel lo bendijo. Parte de esa bendición fue el cambio de su nombre. A partir de ese momento Ya’aqob dejó de llamarse Ya’aqob y su nombre fue ISRAEL. ¿Qué significa Israel? Los comentaristas bíblicos están divididos. Mi explicación favorita, que no voy a fundamentar exhaustivamente en este momento, es que Israel significa: «el que se enfrenta ( o es atacado, como le pasó a Ya’aqob) y pelea con hombres y comunes o poderosos, y prevalece, con la ayuda de HaShem» . («Isra»: prevalecerá, «E-l», con la ayuda de haShem»). Este es el nombre que alentó a Ya’aqob cuando tuvo que enfrentarse en lo que podría haber sido un combate a muerte con su hermano Esav. Israel pasó a ser no sólo el nuevo nombre de nuestro patriarca Ya’aqob sino que por extensión se transformó en el nombre de la nación judía. Nos llamamos el Pueblo de «Israel». Y creo que pocos nombres podrían definir al pueblo de Israel de una manera tan precisa.

Pero más allá de este hermoso significado ¿Por qué el pueblo judío adoptó solamente el nombre del último patriarca? ¿Por qué no nos llamamos el pueblo de Abraham, en honor al fundador del pueblo judío ? O a lo mejor tendríamos que honrar a Itzjaq, que representa a la generación intermedia, la más difícil de mantener. Algo más: la judeidad de una persona se establece vía materna. O sea que para el judaísmo es la madre quien determina la religión de sus hijos. Y si la madre es tan importante en la determinación de la judeidad ¿por qué no nos llamamos el «Pueblo de Sará» o de Ribqá o de Rajel o de Leá? En otras palabras: ¿Por qué nos llamamos ISRAEL y dejamos de lado a todos los demás patriarcas y matriarcas?

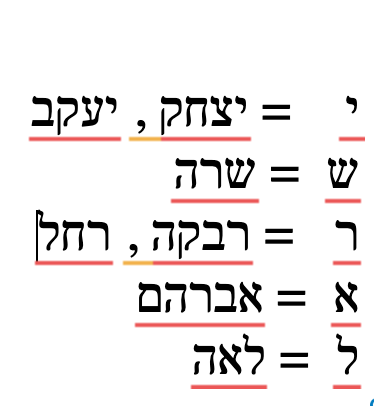

Observemos cuidadosamente la palabra ISRAEL, en hebreo ישראל. Y encontraremos algo maravilloso (e increíblemente poco difundido) que difícilmente puede ser atribuido a una «interpretación» arbitraria o a una «casualidad»: El nombre ISRAEL, en hebreo, contiene las iniciales de TODOS nuestros 7 ancestros: los 3 patriarcas y las 4 matriarcas.

Veamos: La primera letra YOD es la inicial de Itzjaq y de Ya’aqob. La segunda letra, SIN, es la inicial del nombre de nuestra primera matriarca Sará. La RESH corresponde a la primera letra de Rajel y de Rivká. La letra ALEF es la inicial de Abraham y finalmente, la letra LAMED, es la primera letra de nuestra matriarca LEAH. Lejos de excluir a los nombres de los otros patriarcas ISRAEL es el nombre perfecto para nuestro pueblo, que incluye a nuestros 3 patriarcas y 4 matriarcas.

Un famoso Midrash describe a Téraj, el padre de nuestro patriarca Abraham, como fabricante y vendedor de ídolos. En una ocasión, Téraj le pidió a su hijo que lo reemplazara en el negocio. Una clienta trajo un poco de harina como ofrenda para los ídolos, y Abraham aprovechó la ocasión para hacer algo dramático: destruir los ídolos de su padre. Pero eso no fue todo; Abraham también buscaba desenmascarar la falsedad de su progenitor. Cuando su padre regresó y vio la destrucción de su preciada mercadería, Abraham le explicó que los ídolos se habían peleado entre sí, compitiendo por la ofrenda de harina. El Midrash relata la reacción de Téraj ante esta respuesta: “¿Te estás burlando de mí? ¿Acaso pueden los ídolos saber algo o actuar por sí mismos?” A lo que Abraham respondió: “¿Eres consciente de lo que tus propias palabras admiten? [es decir, que los ídolos no tienen vida ni poder alguno]”. Enfurecido, Téraj entregó a su hijo Abraham a las autoridades gubernamentales: el rey Nimrod.

Analicemos brevemente este profundo Midrash.

El negocio de la superstición

Basado en esta historia, y usando un poco de licencia literaria, podría afirmarse que Téraj no vendía ídolos a los ricos o a los reyes, sino a personas humildes y pobres, como esa mujer que quizás no contaba con dinero para comprar un ídolo y solo podía ofrecerles un humilde tributo (que luego iría a los bolsillos de Téraj). Los ídolos de Téraj eran el equivalente de lo que hoy llamamos “amuletos o talismanes de la suerte”. Para triunfar en esta industria y vender “pirámides mágicas” a clientes ingenuos, se requiere ser un embaucador profesional y carecer de escrúpulos morales. Según el Midrash, Téraj sabía muy bien que esos ídolos eran inútiles, pero aun así los vendía, abusando de la gente humilde que venía desesperada en busca de soluciones mágicas en momentos de enfermedad o extrema pobreza. El oficio de Téraj exigía una falta absoluta de honestidad intelectual, falta de sentimiento de culpa o falta de empatía hacia el sufrimiento ajeno. Téraj explotaba a los pobres, sabiendo que cuanto mayor era la vulnerabilidad de su cliente, más fácil era sacarle dinero, harina o servicios para su beneficio.

Sacrificar el futuro económico

Desde niño, Abraham conocía la trastienda de la idolatría y percibió el doble discurso de su padre: alabar los poderes mágicos de los ídolos frente a sus clientes y, en privado, reconocer que todo era un negocio. Gracias a su conocimiento del trasfondo lucrativo de la idolatría, Abraham le perdió el miedo a los ídolos y a las supersticiones populares. Y en un dramático acto de liberación espiritual, Abraham fue capaz de desafiar a su propio padre, consciente de que tendría que pagar un alto precio. Al destruir los ídolos sacrificó la fuente de ingresos estable y próspera que en el futuro heredaría de su familia. Esta honestidad «costosa» no es algo común: la mayoría de las personas en una situación similar, creo, probablemente optarían por cerrar los ojos, autoengañarse y continuar con la lucrativa industria familiar. Pero Abraham era diferente. Su compasión hacia los pobres le generó una intolerancia visceral hacia los embaucadores con fines de lucro o, como los llama el presidente argentino Javier Milei: los “gerentes de la pobreza”.

Cuando el rey Nimrod…

La compasión lo llevó a la honestidad, y la honestidad lo transformó en alguien que literalmente estuvo dispuesto a pensar con libertad. Distinto al resto del mundo, a pesar de las costosas consecuencias. Y las consecuencias no tardaron en llegar. En un acto no menos dramático, su propio padre, Téraj, lo denunció y lo entregó a las autoridades, el tirano rey Nimrod, quien no solo apoyaba a los explotadores de la idolatría sino que era su principal socio y beneficiario. Nimrod sentenció a Abraham, quien solo pudo salvarse gracias a la intervención de “las fuerzas del cielo”.

Causas y efectos

La compasión de Abraham, su reacción alérgica hacia la corrupción y su intolerancia ante el abuso, lo liberaron de la idolatría, pero también lo alejaron de la sociedad pagana. Abraham, se mantenía del lado de la verdad, pero estaba solo. Hasta que un día se encontró con Él –o fue encontrado por Él–y escuchó que le decía, «Abraham: LEJ LEJA, deja la casa de tu padre y ve a la tierra que te mostraré. No te preocupes por tu futuro; Yo estaré contigo. Y haré que te transformes en el patriarca de una gran nación”. Y lo demás es historia. La historia de un pueblo digno de Abraham. Nuestra historia.

Shabbat Shalom

Rab Yosef Bittón

Dedicado al presidente argentino, Javier Milei, y a todos aquellos que luchan contra la corrupción y la deshonestidad.

הכריזו בסדום ואמרו: כל מי שהוא מחזיק ידו בפת לחם לעני לגר ולאביון יישרף באש

LA PEOR DECISIÓN DE TU VIDA

Lot y Abraham vivían en la misma zona geográfica. Pero cuando los pastores de Abraham y de Lot se pelean por territorio, Abraham le sugiere a Lot que cada uno tome caminos separados. «Mira la tierra que está frente a ti», le dijo Abraham a su sobrino, «y elige dónde quieres ir … Si eliges ir para el norte, yo iré para el sur. Y si eliges ir hacia el sur, yo iré hacia el norte». Lot no lo dudó y eligió establecerse en Sedom (Sodoma). ¿Por qué? Porque Sedom era una ciudad de riqueza y estabilidad económica. En ese entonces, esa área poseía abundantes ríos que surgían del Jordán, como el paradisiaco delta del Nilo egipcio, dice explícitamente la Torá. Los habitantes de esa próspera ciudad no dependían de la lluvia, y las sequías no los afectaban. Seguramente Lot imaginaba que allí, en Sedom, iba a construirse una hermosa casa, iba a tener el mejor carro, y casarse él y sus descendientes con familias de mucho dinero. ¡Qué vida tan exitosa le esperaba a Lot en Sedom!

SODOMA Y EL TERCER REICH

Pero la Torá también advierte que las personas de Sedom eran realmente malas y egoístas. No dejaban que nadie compartiera sus riquezas. Y en lugar de asistir, oprimían y explotaban a los extranjeros oa cualquiera que no perteneciera al exclusivo club. Los Jajamim dijeron que en Sedom se estableció una ley que decía que «aquel que ayudase a un pobre, a un huérfano o a un extranjero sería ejecutado». La filosofía de Sedom siempre me hizo acordar al pensamiento de Nietzsche, que luego adoptó el Tercer Reich: al débil o al enfermo no se le tenía que tener compasión y asistir, ya que esto representaba un desperdicio de los recursos del estado. La sociedad Aria debía deshacerse de los más débiles –y así lo hicieron– y dedicar todos sus recursos al progreso de los hombres y mujeres sanos, aplicando una ley natural elemental aprendida de Darwin: la supervivencia del más fuerte.

LA IMPORTANCIA DEL MEDIO AMBIENTE

Lot venía de un ambiente que no podía ser más diferente a Sedom. Lot había sido criado en el hogar de Abraham Abinu. En una casa abierta para todos los necesitados. Lot tuvo que haber absorbido estas lecciones de Abraham. Y me imagino que cuando Lot se dio cuenta de la naturaleza de los habitantes de esa ciudad, se habrá preguntado a sí mismo: ¿Y ahora qué hago? ¿Me quedo en esta ciudad o me voy de aquí? Lot decidió quedarse. Quizás pensó que él tendría la fortaleza emocional suficiente como para no dejarse influenciar por los demás…. Pero se equivocó. Y si bien es cierto que conservó algunas de las características de Abraham, por ejemplo, recibió a extranjeros (malajim) arriesgando su vida, vemos que todo lo hizo solo. A diferencia de Abraham, que junto con su esposa Sará prepararon el banquete para sus visitantes, la esposa de Lot no aparece… él mismo, y solo, tuvo que preparar la comida para sus huéspedes. Es decir: Lot ni siquiera pudo influir en su propia familia. Su esposa y sus hijos, porque la cultura de Sedom ya se había hecho parte de los valores de ellos. Cuando Abraham le pidió a Dios que no destruyera la ciudad de Sedom si se encontraban en la ciudad 10 personas justas, Abraham estaba pensando en Lot y su familia: él, su esposa, sus dos hijas casadas, sus maridos, y sus dos hijas solteras y sus prometidos. Eran en total 10 personas. Pero Dios al final destruye la ciudad porque estas 10 personas no eran individuos justos y rectos. Lot, por más que lo intentó, no pudo aislar a su familia de la corrupción de Sedom. Y lo que es más:Lot ofrece a sus propias hijas solteras para que los habitantes de la ciudad las violen, lo que deja en claro que, en realidad, Lot mismo terminó influenciado por la inmoralidad de Sedom. Se transformó, sin darse cuenta, en una víctima más de la cultura Sodomita.

SAPO A LA CASSEROLE

Una de las lecciones más importantes que escuché en mi vida es la del sapo hervido. ¿Cómo se cocina un sapo?(No sé si esto es verdad o es una leyenda urbana, pero en cualquier caso, por favor, no lo intenten en sus casas, ya que aparte de ser tremendamente cruel, no es Casher :). Para los franceses y los chinos, el sapo a la cacerola es un manjar exquisito. El tema es que al sapo hay que cocinarlo, ¡mientras el sapo está vivo! ¿Cómo se cocina al sapo? Si se lo pone directamente en agua hirviendo, el sapo inmediatamente saltará afuera de la olla. Pero si se coloca al sapo vivo en una olla con agua a temperatura ambiente y a fuego lento, ¡el sapo no se escapa de la olla! ¿Cómo puede ser?

NOSOTROS Y EL SAPO

El cuerpo del sapo puede detectar cambios de temperatura drásticos. Por eso, si de una temperatura de 20 grados lo exponemos a los 100 grados de agua hirviendo, saltará para afuera. Sin embargo, el cuerpo del sapo tolera «pequeños» cambios de calor, se adapta a la nueva temperatura y es incapaz de «sumar» esos pequeños cambios en su cerebro y detectar un gran cambio. Me explico: una vez que el sapo está en el agua y el fuego lento lleva la temperatura del agua de 20 a 25 grados, su cerebro de sapo le dice: «5 grados no es nada. No hay peligro.» Y se adapta a los 25 grados. Cuando el agua llega a los 30 grado, su cerebro, ya adaptado a los 25, le dice al sapo: «son solo 5 grados más, no es nada». Y cuando llega a 35, dice lo mismo: «5 grados, no me afectan». ¡El sapo va tolerando y adaptándose a esos pequeños cambios y es incapaz de sumar esos cambios y decirse a sí mismo: «De 20 a 45… son 25 grados! Esto no me está gustando nada, y puede terminar mal»,Finalmente, cuando llega a los 100 grados, ya es demasiado tarde para el sapo….

CAMBIAR SIN QUE SE NOTE

Con los seres humanos pasa algo muy parecido en el campo de las«influencias». Si nos rodeamos de personas malas, por ejemplo,comenzamos a absorber esos valores de forma muy gradual. Tan gradual que es casi imperceptible percibir los cambios. Con el tiempo, nos pasa como al sapo: No percibimos que los pequeños cambios se van sumando. Y cuando nos queremos dar cuenta, ya es demasiado tarde. Lo bueno es que este mismo principio sucede cuando nos rodeamos de gente buena: los pequeños cambios son imperceptibles en el día a día, como cuando un adolescente crece en estatura o como cuando nos ponemos viejos. La lección que aprendemos de Lot es que tenemos que elegir con mucho cuidado el ambiente donde vivimos,y dónde nos educamos y criamos a nuestros hijos. ¡Que no nos pase como a Lot, o al sapo!